- INTRODUCTION

- LECTURES

- Miles Glendinning / The Hundred Years War: a ‘Long Century’ of Mass-Housing Campaigns Across the World

- Auguste Van Oppen and Marc Van Asseldonk / Open-Source Urbanism

- Tim Rienets / Less Is More? Urban Design and the Challenge of Shrinking Cities

- Adam Bobbette and Etienne Turpin / Aberrant Architecture: Typologies of Practice

- Matthias Rick / Fleeting Architecture ‒ Raumlabor’s Instant Urbanism

- ESSAYS

- Nerijus Milerius / Breaking Point: from Soviet to Post-Soviet City

- Benjamin Cope / A Reflection on Breaking Points in the Case of The Praga District of Warsaw

- Miodrag Kuč / Berlin. Becoming Normal?

- Mindaugas Pakalnis / Vilnius. The Challenge of Disintegration

- Siarhei Liubimau / Popular Urbanism and the Issue of Egalitarianism

- INTERVIEWS

- No Trust – No City / Matthias Rick Interviewed by Ona Lozuraitytė and Aistė Galaunytė

- The Man, Who Turned the Barbeque into the Center of the World / Benjamin Foerster-Baldenius

- Radicalising the Local / Jeanne Van Heeswijk Interviewed by Kotryna Valiukevičiūtė

- Learning-By-Doing / Laura Panait Interviewed by Arnoldas Stramskas

- Preserving the Generic / Kuba Snopek interviewed by Marija Drėmaitė

- A Permanent Anticipation of Uncertainty / Adam Bobbette interviewed by Arnoldas Stramskas

ALF 03

MILES GLENDINING / The Hundred Years War: a ‘Long Century’ of Mass-Housing Campaigns Across the World

Ho Man Tin Estate, Hong Kong. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2011

In this paper, I would like to present an introductory overview of a major research initiative I’ve been working on for a couple of years or so, partly under the aegis of DOCOMOMO International’s Committee on Urbanism and Landscape, and partly as an academic research initiative based at University of Edinburgh. The focus of this initiative is the huge programmes of modern mass housing or public housing, built in countries across the world since the early 20th century. And its aims are to try to trace the reasons for their construction, and document the built environments that resulted: I should emphasise that my concern is with the development, the production of mass housing, and not specifically with the subsequent experience of those environments by its inhabitants – another vast subject altogether, calling on other skills than mine.

Now although this is a kind of built-environment that seems at first glance all too obvious and unambiguous, it actually is quite complicated even to define it at all, to distinguish it from various sorts of private housebuilding. Modern mass housing I define for working purposes in the following rather unwieldy manner: large-scale housing programmes backed in some way or another by the state, whose built form usually involves large aggregates of buildings laid out in the diverse ways allowed for in the modern movement – and usually also involving a degree of egalitarianism and disciplined repetition.

Now until recently this vast and many-sided movement, whose built results are physically so obvious on a vast scale right across the world, and a subject of burning public debate and controversy within many individual countries, has hardly been appreciated as a global discourse at all. To fully get to grips with the global ‘campaign’ of building mass housing, we need to grasp from the beginning that this is not just an architectural style but a vast cultural and political movement, of many aspects and many layers – not least in its diverse interrelationship between international and local/place-specific elements.

The failure to appreciate mass housing as a global, but also locally diversified discourse is seen not least in the current state of academic and more popular coverage of this subject. Up till recently, historical and contemporary-policy discussion of the phenomenon of the building of mass housing, while of course always acknowledging its huge scale and its worldwide spread, still on the whole has tended to address the subject in a geopolitically and culturally compartmented way. Investigations have normally been contained within, and assumed the normative status of, one of three main ‘regions’ of mass housing: Western Europe, the Eastern (postwar socialist) bloc, and North America. As a result, subtle biases and exclusions have often been built in. For example, the Eastern European studies you will all be familiar with have often been dominated by a stress on command production and standardized prefabrication: it’s taken for granted that mass housing will be industrially produced, hyper-repetitive and socialist in its political base. Western European accounts, on the other hand, have been preoccupied by the many solutions of extreme architectural or political individualism. And North American writers have often taken for granted a stigmatized status for public housing from the start, seeing it as doomed by intractable racial tensions. Everywhere else – even active public housing centres like Brazil or Algeria – have tended to be either judged by one of these value-systems or omitted altogether.

More recently, some initiatives like the ‘Constructed Happiness’ conference of 2005 in Tallinn or a DOCOMOMO-International/EAHN mass housing conference we held in September 2011, have made strenuous efforts to draw together the Eastern and Western European narratives in the wake of developments since 1989, setting both in the common geopolitical/historical context of the Cold War. But those unifying efforts have only bolstered, in turn, another ingrained, Eurocentric consensus, a chronological one – that mass housing is a thing of the past, a narrative no longer in active development since 1989 or some other terminal date, an awkward legacy whose main challenge is one of management, even heritage management.

Can this synthesizing trend be taken further forward still, to try to arrive at some sort of totalising narrative that will adequately convey the global reach of this vast effort since the early 20th century? Here the obvious risk is of descending into sweeping and vacuous generalizations. But maybe in an overview paper such as this, one can claim a measure of licence. What I intend to do, allowing for an element of rhetorical exaggeration, is to argue that mass housing was, and is, above all a movement energized and permeated by the rhetoric and values of conflict, war and emergency – and, moreover, one which is not a quiet, tamely dead ‘heritage’ but which still carries on its fights and struggles to new, 21st century battlefields of ‘homes for the people’. I call this movement the ‘Hundred Years War’ – a title borrowed from the medieval history of France and England – because, I would argue, all these different aspects of mass housing had in common a campaigning fighting spirit, drawing their strength from dynamic struggle. A spirit of struggle towards some high goal of salvation, driven forward not by measured advocacy and slow evolution but almost always by emergency ethos of threat and mobilization, strong demand waves, convulsive action: conflict was intrinsic to mass housing, both against external bogeymen such as ‘the slums’ or ‘bad landlords’ but also among the many competing agencies. Often, these were not movements emphasizing individual motivation or liberty, but highly structured, requiring significant coercion in relation to ‘subject’ populations of various categories: we will return later to the question of whether the Hundred Years War has been a defensive or offensive war.

This research programme on global mass housing is aimed at fleshing out this story at a more detailed, scholarly level, and beginning the construction of a coherent, authoritative narrative, that will embrace both the full global scope and chronological span of the entire movement – from its large-scale beginnings after World War I to its late and ongoing renaissance in Asia. Judging by early results, this narrative seems likely to involve a two-speed framework. On the one hand, one finds furious energy and campaigning in intense ‘hotspots’ (often in relatively isolated or beleaguered political or demographic settings) energised by a typically ‘20th-century’ sense of collective emergency, external menace and mass mobilization into establishing unusually resilient housing policies spanning several generations and still enduring today: ‘Red’ Vienna, Hong Kong and Singapore are obvious candidates! On the other hand, there a less dramatic hinterland of subsidiary phases and regions. The task of putting together this story is not just historical – exploiting archives and interviews with surviving participants – but also archaeological, involving documentation of vast areas partly overlaid by later demolitions and ‘regeneration projects’. And this narrative, in turn, might conceivably help inform research in areas that I am not concerned directly with – including the experience of habitation by the residents, or the challenges of today, such as heritage management and housing policy.

To help put together this narrative of global housing production, a range of research initiatives are currently under development both within DOCOMOMO International’s International Specialist Committee on Urbanism and Landscape, and in our department at the University of Edinburgh (the Scottish Centre for Conservation Studies), focusing above all on the initial challenge of constructing a global historical narrative of mass housing, including both the focal highlights of production struggle and the less dramatic areas of everyday regional and cultural diversity ‘in between’.

Now as I suggested above, the overview framework with which I’m trying to make sense of this monumental story of a century’s incessant struggle, commencing around 1914 and continuing in places even today, is based around the idea of incessant campaigning, collective mobilization and dynamic warlike action, expressed in slogans like ‘the battle against the slums’ or the ‘housing drive’. My concept, doubtless rather polemically simplistic, is of mass housing as a ‘world war’, a global conflagration that has spanned the century from 1914 to the present – a world war that fanned out like its real military counterparts from fractures and emergencies in Europe and ‘The West’ into countless regional conflicts, ‘flare-ups’ and campaigns. This was a war fought on ‘fronts’ right across the developed world, wherever the demographic and social pressures of rapid modernization pushed the ‘housing problem’ to the top of the political agenda. And it is a war that is still underway today, on a new ‘front’ in booming Eastern Asia. Some key threads of this conflict are a little unfamiliar to us today, not least the fact that while the ethos of mobilization always presupposed some kind of collective action, it did not always or even mainly presuppose a specifically socialist collectivism; some of the most effective mass housing campaigns were waged by fiercely anti-socialist administrations, whether in New York, Seoul or Singapore, and many of the most vigorous state-sponsored mass housing efforts were concerned not with low-rental dwellings for the ‘poor’ but with the promotion of middle-income ‘home-ownership’.

1920s municipal housing project in ‘Red Vienna’. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2011

1920s municipal housing project in ‘Red Vienna’. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2011

The Old Western Front

The origins of the Hundred Years War lay in the industrialised countries, both of colonial Europe and also of North America. In both cases, the years around World War I had witnessed a sudden and dramatic congruence of the ever more impassioned public discourse of ‘slum housing’ and the new state-led ethos of warlike national mobilization and action. In a new age of concerted ‘national effort’, gross housing inequalities seemed ever more intolerable, and also increasingly possible to remedy by new administrative and scientific interventions. The late 19th century had confined itself to sanitary regulation of private housebuilding, but now a far more active engagement was demanded, especially in reaction to the local housing crises generated by massed movements of war workers.

But from the start, despite all the rhetoric of collective discipline, the patterns of government-sponsored housing campaigns that evolved in Western countries were highly diverse. The most dramatic efforts were those by socialist-dominated city municipalities. They assembled often substantial directly-built and managed housing stocks, which very often prominently featured large blocks of flats of reasonably ‘modern’ types: in this area the unchallenged leader was the famous ‘Red Vienna’ of the 20s, an island of social-democratic energy within conservative, but decentralized, Austria, whose housing memorialized itself and its ‘Austro-Marxist’ community socialist spirit through huge inscriptions and monumental courtyard blocks.

Elsewhere, the concept of municipal social housing was significantly extended in many other countries, especially in Great Britain: here the emphasis on direct municipal provision was applied across the whole country, although with lesser political urgency and more conservative housing types: the classical tenement blocks built by the regional ‘London County Council’ exemplified the ambivalent attitude towards tall, dense flats. By contrast, the 1920s housing sponsored by the municipality of Frankfurt, its design process dominated by architect Ernst May and equally low-rise in emphasis, was in the vanguard of the Modernist ‘New Objectivity’, with its architectural concepts ideas of ‘scientific’ or ‘Functionalist’ planning of dwellings and neighbourhoods. In most countries, however, the emphasis was on a relative continuity with, rather than rupture from, the 19th century patterns, aided by government ‘enabling’ of private or philanthropic efforts: in Europe, it was laissez-faire Belgium that most strongly and consistently favoured this approach.

Over the Hundred Years War as a whole, it was above all North America that put the greatest emphasis on the continuing primacy of private builders, helping them by extensive government grant or tax concessions. For a while, though, that changed dramatically, in the years of the Depression and New Deal. Even as the fascist countries offered one response to the crisis, by prioritizing grand urban-replanning schemes which downgraded social housing to a low priority, the United States embarked on a vast, 15-years’ adventure of planned social building programmes, prominently featuring municipal and federal ‘housing authorities’ (operating from the start within very tight financial constraints) and embarking on massive construction programmes of rather utilitarian multi-storey blocks.

In the US, a strategy such as this New Deal public housing campaign, which ran directly counter to mainstream American values of housing individualism, almost immediately ran into severe problems of stigmatization and decline, compounded by the influence of racial segregation. As early as the late 1940s the United States would begin a prolonged retreat from mass social housing – with one very prominent exception, that of New York. Here the civic regimes of Mayor La Guardia and chief planner Robert Moses significantly enhanced the role of public housing and planning in the city. And by the early 1960s, while straightforward public housing in most US cities was usually targeted at a poor ‘residuum’, the largest-scale developments were being constructed by hybrid private-public or philanthropic agencies – most famously in the case of New York’s gigantic middle-income ‘Mitchell-Lama’ and ‘Title 1’ housing projects of the 1950s–70s, such as the 15,000-dwelling ‘Co-op City’, 1965–72.

Ironically, it was not in New York but in the planned townships of North America’s ‘other’ metropolitan region (created in 1954), Toronto, that the continent’s private enterprise-dominated housing system succeeded in generating a city-wide landscape of massed towers and slabs (up to 35 storeys or more) in open space – one of the world’s foremost hotspots of postwar mass housing. The prerequisites for this were a healthy private-rental market in general, comprehensive government mortgage finance facilities, and a structure of strong regional planning focused on the fostering of high-density focal developments in both the centre and on the vast periphery. In Latin American countries such as Brazil or Mexico, the private sector was yet more dominant, with multi-storey public housing blocks confined to isolated outcrops, although, as in the case of Brasilia’s renowned ‘superquadra’ apartment-block complexes, private-sector operations were successfully reconciled at times with strong planning and architectural frameworks. We will briefly return later in the paper to the question of whether the Hundred Years War also included a campaign front in the ‘Global South’, and, if so, how effective this campaign really was.

Low-rise 1960s–70s developments in Greater Copenhagen: farum Midtpunkt. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2011

Low-rise 1960s–70s developments in Greater Copenhagen: farum Midtpunkt. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2011

The New Western Front

After 1945, even as the United States began retreating from mass state social building and provision, the resurgent nations of Western Europe were racing in the opposite direction, with an often furious energy. This, of course, was a time not of colonialism but of decolonization, and in these former imperialist countries, in some respects the housing and planning drives created new, substitute, domestic ‘empires’. But in postwar Western Europe, just as before, there was still a vast diversity of approaches, both between and within nation-states – for example, between dirigiste and decentralized production methods, between emphasis on social rental and social home-ownership, or in built form between industrial mass production and lavishly-crafted architectural individualism.

Within Britain, for example, the special predominance of the powerful yet decentralized municipal housing system (‘council housing’) ensured that ‘the housing question’ remained a burning local-political issue everywhere. Yet even here there was a wide polarization in approach, between authorities dedicated to individualized architectural design, such as the London County Council and the New Towns, and cities like Glasgow, Liverpool or Dundee, whose council-housing was controlled by engineers and politicians dedicated to maximum output of new dwellings. Elsewhere in western Europe, some countries (such as Sweden) and some individual cities (notably still Vienna) certainly built municipal housing on a major scale, there was a general emphasis on non-municipal solutions of varying types. These ranged from Belgium’s subsidized private builders to West Germany and Denmark’s social housing companies and cooperatives: a few countries, notably Switzerland, built virtually no social housing at all. On the question of where within the urban fabric new public housing should be built, there was a strong polarization between Britain (where much public housing was built on cleared urban redevelopment sites, in the tradition of surgical clearance previously established in city improvement schemes in India and the colonies) and other countries, where large peripheral projects were the norm. In France, a special variant of the latter was evolved and reproduced on a large scale: it involved post-Beaux-Arts layouts of axial slabs and prefabricated slab construction (the ‘grands ensembles’).

As this Western European campaign reached its climax in the mid and late 1960s, some individual developments became almost town-scaled. Examples included Bijlmermeer in the Netherlands or Toulouse le Mirail in France – both involving vast honeycomb-patterns of deck-access blocks – to say nothing of the many explicitly ‘New Towns’ that were under construction at the time. At the same time, there was countless small-scale local variation, as between the often exaggeratedly contrasting housebuilding policies of adjoining boroughs in the Greater London conurbation.

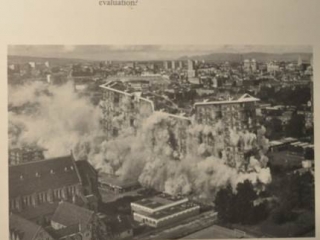

But all patterns of building and all places shared in the ebbing of development impetus in the 1970s. From now on, the public and political pressure for postwar reconstruction was largely satisfied. After the end of the so-called ‘trentes glorieuses’ (the ‘three great decades’) in 1975, some European mass housing became as stigmatized as the ‘new ghettos’ of the USA. A series of milestones of crisis and rejection, began in May 1968 with the partial collapse of ‘Ronan Point’ in London and arguably culminated in the October 1992 crash of an El-Al jumbo jet on two blocks in the Bijlmermeer, in outer Amsterdam.

Late and post-Soviet panel blocks: Konkovo, 1980s. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2013

Late and post-Soviet panel blocks: Konkovo, 1980s. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2013

The Old Eastern Front

At the very time this vast diversity of building programmes was winding down in the West, in the socialist Eastern bloc, things began stirring in earnest, and in a rather different way. Previously, housing had been sidelined by the Stalinist preoccupation with other building tasks – industrialization in the 30s followed by postwar repairs in the late 40s. In the era of Socialist Realism, modernist housing and planning patterns were generally denounced as ‘western’ and ‘bourgeois’. Under Stalin, most housing efforts were confined either to prestige boulevard projects not unlike those of the fascist regimes, or scattered developments built by individual industries. The same fragmented pattern of work and residential compounds, was also taken up by post-1949 communist China, in the form of the ‘dan-wei’ formula of walled workplace and factory housing, and was perpetuated there until the 1980s without significant rupture. The Soviet bloc, by contrast, saw a major rupture in policy and architecture in the later 1950s. Here, the impetus for change was partly internal and political, in Khrushchev’s mid 1950s rejection of Stalinism and demand for a standardized, industrially-produced approach. External professional factors were also important, in the form of the influence of the Western-style Modernist housing and planning approaches introduced to Soviet architects at the 1958 International Union of Architects convention in Moscow.

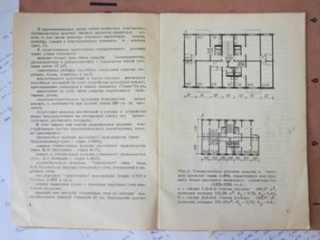

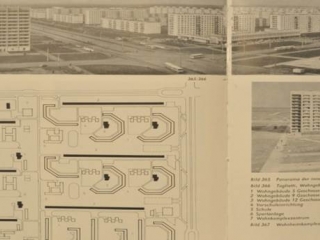

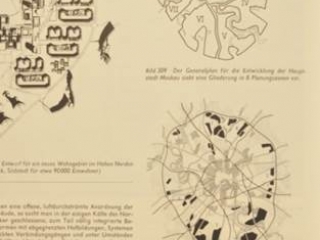

Whatever the immediate causes, the effect was dramatic. As you will all know, within a few years the entire soviet socialist ‘empire’ had embraced the complete package of modernist housing design. This included the US-European ‘neighbourhood-unit’ community planning concept, significantly adapted into the ‘mikrorayon’, as well as the Modernist principles of rectilinear block layouts in open space. The particular layout pattern most commonly generalized in the Soviet bloc owed much to French mass housing modernist principles. These emphasised axially-planned, prefabricated slab blocks of medium height, set in very wide expanses of space – in practice often built without landscaping or planned community facilities owing to resource shortages. In ‘patronage’ terms, the Stalinist pattern of housing developments built by factories or plants became less prominent after the 1950s, although in the case of strategic military-industrial concerns, the scale of development was stepped up into entire planned towns. A more ‘Western European’ style municipal housebuilding structure, including strong planning departments, city architectural design teams and city building combines, emerged to take its place.

The extreme Soviet emphasis on type-plan standardization and prefabrication, although extrapolated from earlier Western precedent, led to a very different, more coarse-grained landscape than that in Western Europe. Here, successive generations of block types – from the 5-storey Khrushchevki of the late 50s to the more variegated towers and slabs of the 1970s–80s – followed one another in cumulative tidal patterns. But ‘local character’ in the Western sense, or (for that matter, in the sense of later Eastern Asia) was largely absent. For example, in Tallinn, in Estonia, most of the mass housing developments of the 1960s, 1970s and 80s are largely concentrated into three very large peripheral developments, Mustamäe (1960s), Vaike-Õismäe (1970s, planned in a huge circle ringed by towers) and Lasnamäe (mostly 1980s, with a largely unrealized ‘sunken motorway spine’). Also sharply divergent from Western Europe was the way in which these patterns also extended to rural areas, in the standardised housing groups and community facilities built for collective farms. Moreover, reflecting socialist egalitarianism, all these developments were intended for occupation by a broad range of social and economic groups, rather than just by the more disadvantaged, ‘residual’ groups.

During the Brezhnev era of the mid 60s – early 80s, driven by the ultimately vain Soviet aspiration to match the West in social provision and in production, this colossal apparatus built up ever greater momentum, pushing through a vast building campaign that stretched right across Eastern Europe and Asia to the Soviet Far East. Construction continued at a high level right through the 80s. All the more dramatic, therefore, was its sudden collapse in the wake of the fall of the Soviet empire in 1989–91 – a phenomenon that Lithuania was one of the first places to experience. Here, unlike the position in the West, decolonization directly impacted on mass housing policy. In the former USSR; almost overnight, housing changed from being an exclusive province of the state to being an object of the most extreme laissez-faire privatism. Overnight, too, the built environments bequeathed by the ‘years of stagnation’ were in many places afflicted by potential obsolescence and decline. In some places, the loss of status and demand was immediate, above all in the former East Germany, where many towns began to lose much of their population to the west, and the following decades saw radical, surgical demolitions like those already well-established in the West. Elsewhere, in many Russian and central/eastern European cities, the picture was more patchy and variegated. Everywhere, though, large-scale privatizations of housing stocks irretrievably fragmented the former cohesiveness and discipline of socialist mass housing.

More generally, by the 1990s the mass-housing environments bequeathed by the postwar ‘housing drives’ in both ‘East’ and ‘West’ seemed to be suffering an increasing range of problems and challenges, including a tendency in many places to social ‘residualisation’. Did this decline of European-American mass housing on both its western and eastern fronts constitute a housing reflection of the then much discussed ‘End of History’? Certainly, within its heartlands, mass housing increasingly became seen as a legacy of the socialist or social-democratic past, whose key challenge was that of managed decline. Correspondingly, heritage perspectives became increasingly prominent: many began to ask whether a cathartic transformation in reception of this heritage might be preferable to the wastefulness of blanket demolition – as a way of expressing appropriate care and respect for collective assets in the widest sense, by both inhabitants and the community at large.

Even as these debates bubbled away in the heartland of mass housing, a new ‘front’ was steadily gathering momentum further to the East, a campaign driven in many places by exactly the same ethos of modernization emergency as in Europe, but expressed in very different forms.

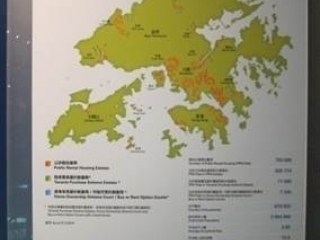

41-storey ‘Harmony’ public rental blocks built in 1998–2002 at Ho Man Tin Estate, Kowloon. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2011

41-storey ‘Harmony’ public rental blocks built in 1998–2002 at Ho Man Tin Estate, Kowloon. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2011

The New Eastern Front

As I explained earlier, post-1949 Maoist China, with its fragmented dan-wei housing pattern, was not itself a centre of conventional mass housing production. But the indirect impact of the communist victory in China elsewhere in the region was striking. Its repercussions included the emergence, from the 1950s onwards, of the most dramatic campaign of the Hundred Years War: the vast housing production efforts of the city-states of Singapore and Hong Kong, micro-territories faced by external political and demographic destabilization. These programmes were paralleled by vigorous but sharply contrasting campaigns of mass housing construction elsewhere in the region, including Japan and (from the 70s) in South Korea.

The colonial context in Hong Kong and Singapore was clear and yet at the same time rather oblique – shaped on the one hand by the decline in British and Japanese imperialism, but on the other hand disrupted by the ideological intrusions of Chinese communism. These mass-housing campaigns, which gathered pace steadily and burst into full flood from the 1970s and 80s, as mass housing was ebbing elsewhere in the world, were, and still are, programmes of a clearly Modernist social mass-provision character. They set themselves squarely in the Modern tradition of architectural mass provision, but far outstripped the old European setpieces of social Functionalism in scale and boldness: even the most utopian European early Modernist visions are dwarfed by the reality of today’s Hong Kong public housing, with its arrays of 41-storey towers. Yet these programmes have a strikingly different political and economic context from their predecessors to the west. For they have been implemented by the two most uncompromisingly capitalist societies in the world, identified by the Heritage Foundation for 17 years running as the world no.1 (Hong Kong) and no.2 (Singapore) in ‘economic freedom’. They have been shaped not by state socialism but by the desire to protect ‘free’ capitalism both from socialism itself, and more generally from demographic and political and ethnic instability – within an Asian cultural context. With the possible exception of Red Vienna away back at the beginning of the Hundred Years War, it was in Hong Kong and, especially, Singapore, that the association between mass housing and the rhetoric of emergency reached its all-time climax.

These colossal programmes began after World War II, when the credibility of European imperialism in the east had been shattered by the Japanese. Immediately afterwards, Hong Kong and Singapore, both classic British colonial entrepot port enclaves, populated largely by ethnic Chinese, were overshadowed by indirect communist destabilization stemming from the takeover of China, and (in Singapore) ethnic divisions: Hong Kong was also, more immediately, threatened by vast waves of refugees.

Over the 1940s–1960s, two somewhat different decolonisation strategies emerged. After much turmoil in the 50s and early 60s, Singapore split off from British rule in the mid 60s as an independent statelet under the rule of the People's Action Party, led by Lee Kwan Yew. The PAP regime exploited public housing as the foundation for an avowedly anti- or post-colonial ideology of autarchic national mobilization against the twin threats of Communist subversion and ethnic factional violence. It is something of an irony that arguably the most ‘political’ housing drive ever was motivated not by socialism but by authoritarian anti-communism. Hong Kong remained under British colonial rule for several more decades. This insulated it as a capitalist enclave from Communist instability on the mainland while the British themselves undertook a behind-the-scenes decolonisation. But in both cases, the administrative method used was basically the same, namely, dirigiste colonial administration modified by the dynamic built-form offshoots of 20th-century European welfare statism - especially town and country planning, and mass social housing. These programmes make an interesting comparison to the vast reconstruction projects of Robert Moses in New York from the 30s to the 60s, which were also driven by a bitter anti-communism and somewhat right-wing authoritarianism.

At first, the vast programmes of public housing and planned settlement in both these two Asian mini-territories from the early 1950s directly stemmed from older colonial patterns. The first large-scale public housing in Hong Kong took the form of barrack-like, H-shaped 'resettlement' blocks built experimentally from 1954 to rehouse squatters. Because of the shortage of land and the incredible demographic pressures created by mass refugee influxes, densities were far higher than anything in European Modernism (up to 3,000 persons per acre). But by the 1960s, this regimented, basic provision was increasingly replaced in both territories by an overtly Modernist mass-housing approach, steered by highly centralized ‘national’ housing authorities (Singapore’s Housing Development Board, or HDB, and the Hong Kong Housing Authority, HKHA).

In Singapore, the more plentiful land supply allowed a more spaced-out planning and housing policy. This involved the building of a ring of new towns (the ‘Concept Plan’) and commencement in 1964 of an ultimately hugely successful programme of HDB building for home-ownership, through a system under which compulsory social-insurance levies could be partly converted into mortgages, to cement the cohesion of a once transient society – a paradoxical ideology of mass mobilization through mass homeownership. A number of European countries (such as Finland, Norway or West Germany) had also long emphasized ‘social home-ownership’ in their national housing strategies, but Singapore took the concept to an unprecedented extreme. Within a quarter of a century, 85% of the population were living in owner-occupied high-rise public housing, much of it styled in a rather Postmodernist rather than Modernist way.

From the mid 70s, the ‘social homeownership’ policy jumped to Hong Kong. There it was taken up with a vengeance by the HKHA, as part of the reformist strategy of governor Murray MacLehose. He initiated a wide range of community-building initiatives to foster social cohesion in the territory following the communist-inspired riots of 1967. Hong Kong’s Home Ownership Scheme, devised by the HKHA’s chief architect and housing director, Donald Liao, was initiated in 1976 to complement MacLehose’s policy of radically expanded public rental production and new town construction. Liao expanded the Singapore formula into a building campaign of gigantic Modernist tower-clusters (ultimately up to 41 storeys): the HOS was suspended in 2002–3 following pressure from private developers against ‘unfair government competition’, but is soon to return again.

In both territories, this Asian association of mass state housing and homeownership has, arguably, realised the classless aspirations of 1920s European Modernism rather better than the class-stigmatised reality of much Western public housing.

Hong Kong also took up from the 70s the Singapore concept of high-density new towns, expanding them to city scale (and populations of several hundred thousand) in developments such as Sha Tin and Tuen Mun. Their planning echoed the late modernist reaction away from the functionally segregated new towns towards more densely nucleated forms and overlapping uses. However, that cluster concept was implemented in Hong Kong with unprecedented intensity and scale, with every large housing project consisting of towers of flats integrated with a large megastructural centre. Here, something new, something arguably deriving from Chinese as much as European urbanism, was created. Even the most dense Western new towns simply could not attain the critical mass of density to really overcome functional segregation; they could not make possible a Modern environment which catered for rising expectations of personal living space, yet consistently integrated people's homes with other uses.

The Hong Kong building drive experienced a temporary ‘European-style’ crisis of confidence in the early 2000s following a massive expansion of the annual building target to 85,000 by the post-1997 administration of Tung Chee-Hwa: local building overstretch culminated in a ‘short piling scandal’ in which two new 41-storey blocks in Sha Tin had to be demolished. But the crisis was weathered, and today, both the Hong Kong and Singapore programmes continue in full force, with the HKHA now focused mainly on rental housing and the HDB on owner-occupation. They are increasingly augmented by others in the region – above all in South Korea, where a huge housing programme of repetitive, parallel apartment slab blocks, built mainly by private firms with state enabling, has got under way since the 1960s, and has boomed especially from the late 1980s. Rapidly building up on an even greater scale is the social housing effort in mainland China, where the vast demographic and social stresses unleashed by the country’s breakneck development over the same period have prompted calls for a similar policy: although the massive public housing drive initiated by disgraced Party chief Bo Xilai in Chongqing has since been reined back in, numerous other mainland Chinese cities are also now embarking on more modestly-scaled public housing programmes.

Hong Kong Housing Authority sign. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2012

Hong Kong Housing Authority sign. Photo: Miles Glendinning, 2012

The Hundred Years War: Issues, Definitions and Omissions

We have seen in this paper how the Hundred Years War has jumped from one campaign theatre to another across the world, flaring into life again as circumstances demanded. But if what we have traced was a kind of war, was this a case of offensive or defensive warfare? To judge merely from its frequently radical redevelopments and population displacements, its enforced resettlements of slum dwellers or squatters, its attempts in the Eastern Bloc to destroy bourgeois society and create Soviet Man, one could certainly put a prima-facie case for the former – for a concept of mass housing as, above all, an agent of destabilization, a means of ‘disembedding’ obsolete social and residential patterns. Equally, however, one could argue that it acted as a defensive bulwark, as a means of containing demographic and social disruption. Although this function was most clearly legible in the programmes of social home-ownership, with their often explicitly articulated values of community-building, it was also, arguably, just as important in the short-term stabilizing role of public rental housing, whether in the aftermath of war or in the face of some other ‘national emergency’. In the housing strategy of someone like Lee Kwan Yew, it’s difficult to separate out ‘offensive’ and ‘defensive’ strategies. The dispersion of the kampong and squatter dwellers into state homeownership flats was seen as a way of both destroying older, less controllable housing patterns and fending off the threat of communist subversion or ethnic destabilization.

Doubtless, one of the key driving forces of modern society since the 18th century has been the quest for freedom and individualism. But the essential companion and counterbalance to this has been a social and collective ethos, which has repeatedly asserted itself at critical emergency times in the process of development, at junctures when the legitimacy or stability of states or societies was called into question. During the past hundred years, during the Hundred Years War, the epoch to be catalogued in my current research initiative, mass housing has formed a central element in that collective response, whether in attack or in defence – and, in the housing programmes of Eastern Asia at least, it looks likely to continue in that role in the future.

What will also require to be investigated in both breadth and depth in this research initiative is what seems, on the face of it, to be the main significant omission from our simplified narrative of ‘campaigns’ – the question of whether there was, or is, a ‘Southern Front’, a ‘campaign’ of mass housing in the ‘Global South’, a loose geographical concept denoting the ‘developing’ and ex-colonial world, which is conventionally taken to include all of Africa, all of southern and central America, and most of Asia. Of course, the demarcation-lines of this definition are subject to constant shifts, not least in Eastern Asia, in the rapid development and, often, decolonization of the countries and territories just discussed; and southern/central America, in the early date of its decolonization and its long-established and often considerably ‘developed’ nations, also presents another huge ‘anomaly’ to any general categorization. Nevertheless, this vast, global assemblage undeniably presents some common features, notably the far more limited scale of state intervention and collective discipline, and the corresponding reliance on unregulated private construction falling outside our definition of ‘mass housing’. Even the largest state social-building campaigns, such as the late 1950s ’23 de Enero’ slab blocks in Caracas, containing tens of thousands of low-income rental flats (and subsequently degenerated into a ‘ghetto’ zone) were rather isolated islands of collective activity in a wider laissez-faire context. In many decolonizing countries in Africa, the building of state-directed mass housing was largely confined to experimental schemes by outgoing colonial regimes (sometimes on a large scale, as in 1950s Algiers), while more recent urban housing has been dominated by laissez-faire patterns – for example, in the huge output of high-density tenements in Nairobi, almost entirely built by small speculators in a pattern similar to late 19th-century Europe. In other cases, state-sponsored construction largely followed low-rise, non-Modernist patterns, as in the garden-city bungalow layouts of the ‘Bantu locations’ of apartheid South Africa, or the state-sponsored social home-ownership schemes of Mexico City – and thus arguably fall outwith the strict boundaries of this research project. In many ways, the chief initial task of the project will be to settle on a workable formula of definitions and demarcation lines, to establish precisely what is to be studied!

DOCOMOMO-International: letterhead of Specialist Committee on Urbanism and Landscape

DOCOMOMO-International: letterhead of Specialist Committee on Urbanism and Landscape

Conclusion: Mass Housing as Heritage – Conservation or Documentation?

I would also, in conclusion, like to briefly make a couple of points about the potential implications of this research initiative for DOCOMOMO, with its double concern for documentation and conservation. This double focus is especially important for mass housing, given the combination of the impracticability of preserving these environments as heritage on any significant scale, and the likelihood of radical redevelopment that faces many of them– constraints which foreground recording all the more. And secondly, while DOCOMOMO is already piloting some ideas about on-line image banks, a more concerted and interactive approach could allow the process to be taken much further forward. The current project is building up potentially a wealth not only of built-form data, including contemporary and historic images and documentary infrmationo, but also issue-related records like interview transcripts with actors spanning periods back to the ‘30s, or copious research notes from archives and record offices. If this initiative, working in conjunction with DOCOMOMO, could act as a catalyst in furthering the systematic inventorisation of mass housing environments, it could significantly advance the cause of global modern heritage.